A cognitive bias refers to a ‘systematic error’ in the thinking process.

Such biases are often considered as a type of heuristic, which is essentially a mental shortcut – heuristics allow one to make an inference without extensive deliberation and/or reflective judgment, given that they are essentially schemas for such solutions.

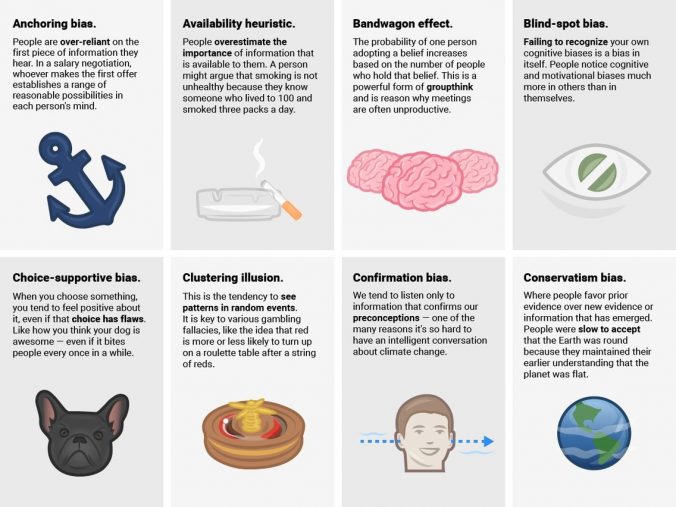

These are not the only cognitive biases out there (e.g. there’s also the halo effect and the just world phenomenon); rather, they are the 12 most common biases that affect how we make everyday decisions, from my experience.

1. The Dunning-Kruger Effect

In addition to the explanation of this effect above, experts are often aware of what they don’t know and (hopefully) engage their intellectual honesty and humility in this fashion. In this sense, the more you know, the less confident you’re likely to be – not out of lacking knowledge, but due to caution. On the other hand, if you know only a little about something, you see it simplistically – biasing you to believe that the concept is easier to comprehend than it may actually be.

2. Confirmation Bias

Just because I put the Dunning-Kruger Effect in the number one spot does not mean I consider it the most commonly engaged bias – it is an interesting effect, sure; but in my Critical Thinking classes, the Confirmation Bias is the one I constantly warn students about. We all favour ideas that confirm our existing beliefs and what we think we know. Likewise, when we conduct research, we all suffer from trying to find sources that justify what we believe about the subject. This bias brings to light the importance of, as I discussed in my previous post on 5 Tips for Critical Thinking, playing Devil’s Advocate. That is, we must overcome confirmation bias and consider both (or, if more than two, all) sides of the story. Remember, we are cognitively lazy – we don’t like changing our knowledge (schema) structures and how we think about things. Notably, confirmation bias is similar to Belief Bias in this respect.

3. Self-Serving Bias

Ever fail an exam because your teacher hates you? Ever go in the following week and ace the next one because you studied extra hard despite that teacher? Congratulations, you’ve engaged the self-serving bias! We attribute successes and positive outcomes to our doing, basking in our own glory when things go right; but, when we face failure and negative outcomes, we tend to attribute these events to other people or contextual factors outside ourselves.

4. The Curse of Knowledge and Hindsight Bias

Similar in ways to the Availability Heuristic (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974) and to some extent, The False Consensus Effect, once you (truly) understand a new piece of information, that piece of information is now available to you and often becomes seemingly obvious. It might be easy to forget that there was ever a time you didn’t know this information and so, you assume that others, like yourself, also know this information. However, it is often an unfair assumption that others share the same knowledge. The Hindsight Bias is similar to the Curse of Knowledge in that once we have this information (i.e. the details of the event), it then seems obvious that it was going to happen all along. I should have seen it coming!

5. Optimism or Pessimism Bias

As you probably guessed from the name, we have a tendency to overestimate the likelihood of positive outcomes, particularly, if you are in good humour or overestimate the likelihood of negative outcomes f you are feeling down or have a pessimistic attitude. Ever hear the expression, ‘Hope for the best, prepare for the worst’? Depending on your mood or attitude, this can potentially be either conscientious, organised advice (positive affect) or perhaps a defense mechanism (negative affect) against a setback. In either the case of optimism or pessimism, be aware that emotions can make thinking irrational. Remember, one of my 5 Tips for Critical Thinking, Leave emotion at the door!

6. The Sunk Cost Fallacy

Though labelled a fallacy, I see ‘Sunk Cost’ just as much in tune with bias as faulty thinking, given the manner in which we think in terms of winning, losing and ‘breaking even’. For example, we generally believe that when we put something in, we should get something out – whether it’s effort, time or money. With that, sometimes we lose… and that’s it – we get nothing in return. A sunk cost refers to something lost that cannot be recovered. Our aversion to losing (Kahneman, 2011) makes us irrationally cling to the idea of ‘regaining’, even though it has already been lost (known in gambling as chasing the pot – when we make a bet and chase after it, perhaps making another bet to recoup the original [and hopefully more] even though, rationally, we should consider the initial bet as out-and-out lost). The appropriate advice of cutting your losses is applicable here.

7. Negativity Bias

Negativity Bias is not a totally separate entity to Pessimism Bias, but it is subtly and importantly distinct. In fact, it works according to similar mechanics as the Sunk Cost Fallacy in that it reflects our profound aversion to losing. We like to win, but we hate to lose even more. So, when we make a decision, we generally think in terms of outcomes – either positive or negative. The bias comes in to play when we irrationally weigh the potential for a negative outcome as more important than that of the positive outcome.

8. The Decline Bias (aka Declinism)

You may have heard the complaint that the INTERNET will be the downfall of information dissemination; but, Socrates reportedly said the same thing about the written word. Declinism refers to bias in favour of the past over and above ‘how things are going’. Similarly, you might know a member of an older generation who prefaces grievances with ‘Well, back in my day’ before following up with ‘how things are getting worse’. The Decline Bias may result from something I’ve mentioned repeatedly in my blogs – we don’t like change. People like their worlds to make sense, they like things wrapped up in nice, neat little packages. Our world is easier to engage when things make sense to us. When things change, so must the way in which we think about them; and because we are cognitively lazy (Kahenman, 2011; Simon, 1957), we try our best to avoid changing our thought processes.

9. The Backfire Effect

The Backfire Effect refers to the strengthening of a belief even after it has been challenged. Cook and Lewandowsky (2011) explain it very well in the context of changing people’s minds in their Debunking Handbook. The Backfire Effect may work based on the same foundation as Declinism, in that we do not like change. It is also similar to Negativity Bias, in that we wish to avoid losing and other negative outcomes – in this case, one’s idea being challenged or rejected (i.e. perceived as being made out to be ‘wrong’) and thus, they hold on tighter to the idea than they had before. It is also similar to the Reactance Effect. However, there are caveats to the Backfire Effect – for example, we also tend to abandon a belief if there’s enough evidence against it with regard to specific facts; though nevertheless, the ‘parent’ belief or another related belief may actually be strengthened as we attempt to restructure our understanding.

10. The Fundamental Attribution Error

The Fundamental Attribution Error is similar to the Self-Serving Bias, in that we look for contextual excuses for our failures, but generally blame other people or their characteristics for their failures. It’s also a bias stemming from the Availability Heuristic in that we make judgments based only on the information we have available at hand. One of the best text-book examples of this integrates stereotyping: Imagine you are driving behind another car. The other driver is swerving a bit and unpredictably starts speeding up and slowing down. You decide to overtake them (so as to no longer be stuck behind such a dangerous driver) and as you look over, you see a female behind the wheel. The Fundamental Attribution Error kicks in when you make the judgment that their driving is poor because they’re a woman (also tying on to an unfounded stereotype). But, what you probably don’t know is that the other driver has three children yelling and goofing around in the backseat, while she’s trying to get one to soccer, one to dance and the other to a piano lesson. She’s had a particularly tough day and now she’s running late with all of the kids because she couldn’t leave work at the normal time. If we were that driver, we’d judge ourselves as driving poorly because of these reasons, not because of who we are. Tangentially, my wife is a much better driver than I.

11. In-Group Bias

As we have seen through consideration of the Self-Serving Bias and the Fundamental Attribution Error, we have a tendency to be kinder to ourselves when making judgments about our successes and failures. This extends to those we hold near and dear, those who we perceive as similar and those who we consider part of our ‘group’. Simply, In-Group Bias refers to the unfair favouring of someone from one’s own group. You might think that you’re unbiased, impartial and fair, but we all succumb to this bias, having evolved to be this way. That is, from an evolutionary perspective, this bias can be considered an advantage – favouring and protecting those similar to you, particularly with respect to kinship and the promotion of one’s own line.

12. The Forer Effect (aka The Barnum Effect)

As in the case of Declinism, to better understand the Forer Effect (commonly known as the Barnum Effect), it’s helpful to once again acknowledge that people like their worlds to make sense, they like things wrapped up in nice, neat little packages and patterns. It’s easier this way – for our world to make sense to us, because if it didn’t, we would have no pre-existing routine (i.e. heuristic) in which to fall back on and we’d have to think harder to contextualise this new information into our world. With that, if there are gaps in our thinking of how we understand things, we will try to fill those gaps in with what we intuitively think makes sense, subsequently reinforcing our existing schema(s). As our minds make such connections to consolidate our own personal understanding of our own personal worlds, it is easy to see how people can tend to process vague information and interpret it in a manner that makes it seem personal and specific unto them. Given our egocentric nature (along with our desire for nice, neat little packages and patterns), when we process vague information, we hold on to what we deem meaningful to us and discard what is not. Simply, we better process information we think is specifically tailored to us, regardless of ambiguity. Specifically, the Forer Effect refers to the tendency for people to accept vague and general personality descriptions as uniquely applicable to themselves without realizing that the same description could be applied to just about everyone else (Forer, 1949). For example, when people read their horoscope, even vague, general information can seem like it’s advising something relevant and specific (and sometimes accurate) unto them.

While heuristics are generally useful for making inferences, through providing us with cognitive shortcuts that help us stave off decision fatigue, some forms of heuristics – cognitive biases – make our judgments irrational.